FS: How was the transition of returning to Mexico after having studied for two years in Estonia?

CC: When I first left Mexico, the pandemic was still ongoing. Two years later, I returned to a place that felt completely different from the one I had left. People had adapted to post-COVID life, and there was a noticeable wave of gentrification, which you experienced too. Prices went up, a surge of graphic designers had emerged, and people from all over the world were moving to Mexico.

I also came back with the expectation that, having completed a master’s degree, things would be easier. On the other hand, returning with a master’s degree led me to teaching. The Director of Visual Communication at Centro, reached out and asked if I could teach a class, and of course, I said yes.

FS: How was it like getting commissioned work again?

CC: It has been challenging to find new projects again, partly because I had become almost completely disconnected from Mexico during my master’s. One advantage, though, was that my thesis, Glory Holes, connected me with people who shared similar interests, many of whom I now collaborate and work with. One of them is César González Aguirre, founder of the Archivo de Memoria Trans (Trans Memory Archive) in Mexico. I interviewed César as part of my research because I wanted to learn more about queer history in Mexico.

When it came to commissioned or commercial projects, it was hard to get back into it. And honestly, it’s difficult to talk about the professional side without also touching on the personal. That’s what made it most complicated, the sense of longing and the hope that things would still be the same. Now, nearly two years after graduating, I feel like I’m only just beginning to find my own rhythm.

FS: How did you connect César while you were in Tallinn?

CC: While I was in Tallinn, Andrea Ancira, the person behind Tumbalacasa Ediciones, got in touch with me via Instagram. She was working on “The Taste of Water,” an exhibition at the Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, where she's currently doing her PhD, and asked if I’d be interested in designing the publication for it. Our physical closeness made the collaboration easier to coordinate.

During one of our meetings, we started talking about our respective projects. I told her about the early stages of what would eventually become Glory Holes. That’s when she said, “You should talk to César, they [Brandy Basurto, Emma Yesica Duvali, Terry Holiday and César González-Aguirre] just founded the Archivo de Memoria Trans in Mexico,” and she shared his email with me.

At first, I felt uncertain about diving into queer history in Mexico because, well, I wasn’t there, and it wasn’t a subject I had previously explored in depth. Most of my research up to that point had come from books and online sources. So it was meaningful to have a one-on-one conversation with someone who had been more involved in this work. Glory Holes explores memory and archival practices within queer history, which closely aligned with the work César was doing.

FS: With projects like Drama or Archivo de Memoria Trans, how have you come to understand the audience in Mexico around these topics?

Drama is a photography vitrine located in Mexico City’s Historic Center, founded by César González Aguirre. Carlo began doing the graphic design for Drama and has since become a collaborator.

CC: It’s definitely a small audience. I can’t speak in detail about the Archivo de Memoria Trans since I’m not formally involved in the project, but I imagine it’s difficult to define a specific audience because the archive mainly exists as an online collection. The current efforts focus more on building an audience rather than catering to an existing one. Thanks to the archive and the people involved, many of whom are artists or connected to the art world, there have been opportunities to exhibit work in various spaces, including galleries and public venues. I believe that engaging with these kinds of institutions or projects, which may be less formal but often more accessible, has played a key role in increasing visibility.

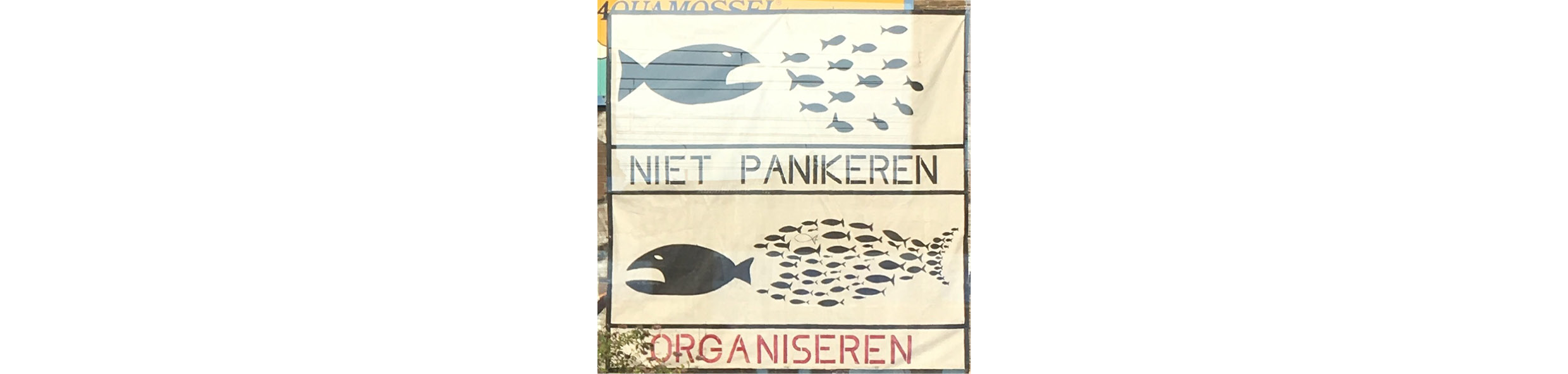

In contrast to the Archivo de Memoria Trans, Drama functions more as a gallery, and by that, I mean a more commercial project, focused on selling artworks and photographs. However, Drama’s vision is to take art out of the traditional “white cube” gallery space and create a project that’s inviting to all kinds of audiences.

Drama is a display window located in the Pasaje Savoy, a passageway in Mexico City’s Historic Center, nestled among a porn cinema, service shops, and long-established businesses. And because of its location, most of its audience consists of passersby rather than visitors who come specifically to see the exhibitions.

I believe Drama has made an impact as a counterproposal to the typical gallery spaces we usually associate with art. In Mexico, there’s often a focus on hype, the polished, and what feels “contemporary,” but Drama intentionally lacks those qualities, in the best way possible.

FS: That’s interesting because it’s situated in a location where most viewers are simply passing by or heading to the cinema. In a way, it might feel less accessible to the audience typically interested in these types of projects, but at the same time, it becomes more accessible to people who might not usually visit a gallery.

CC: And well, another factor affecting accessibility to the space is the city’s layout. The openings used to be on Thursdays but are now held on Fridays, typically at 7 pm, right in the middle of Mexico City’s rush hour. As you know, getting from one place to another in the city is pretty chaotic.

An important aspect of the project is that it reaches people who aren’t necessarily expecting to encounter something like this. The curation and artist program at Drama feature individuals who may not have had this kind of visibility before.

FS: Have all the artists who have exhibited at Drama been Mexican?

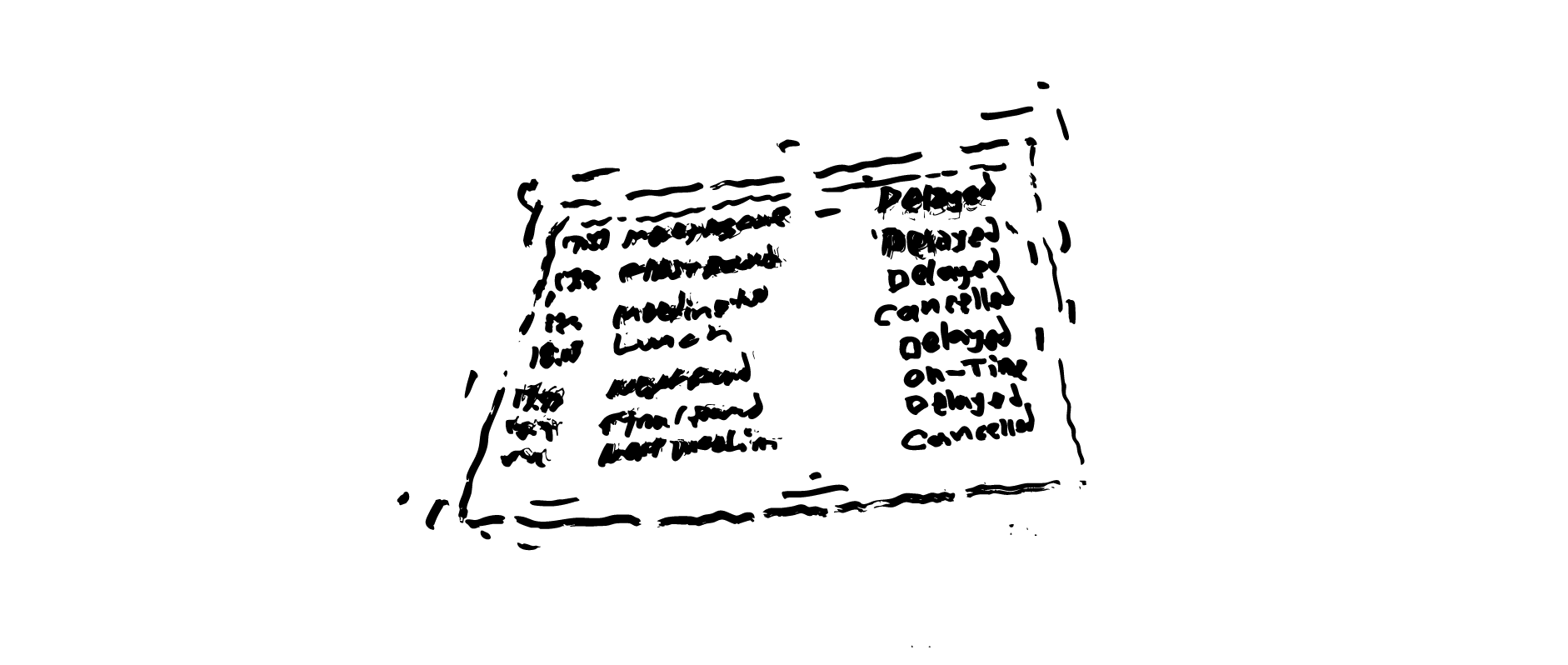

CC: Yes, so far all the artists have been Mexican. For example, one of them is Rafael Manrique, a photographer who worked for Del Otro Lado, a magazine by Colectivo Sol. He captured images in a documentary style that also served as a form of activism. César organized an exhibition with him called Eternidad (Eternity), featuring a selection of male portraits taken in Veracruz during the 1980s and 1990s, marking the first time Rafael’s work was shown in a gallery setting.

In that sense, it’s not necessarily about reaching a large audience. It’s more about offering counterproposals to the canonical or hegemonic narratives dominating the art world.

FS: That sounds really exciting. What has your experience been with queer archives in Mexico?

*Maricoteca is a self-managed archive dedicated to the material culture of sexodiverse lives in Mexico and Latin America.

CC: Well, there’s definitely a problem in Mexico when it comes to preserving and sharing memory. One major issue is that, while some institutions do hold important materials, accessing them is extremely difficult. For example, you might be required to submit a request form three months in advance, detailing exactly which materials you want to consult.

There are also private collections, archives kept in people’s homes or held by individuals. And there’s a lot of gatekeeping, right? Gaykeeping. Some people are very protective and unwilling to share what they have. On the other hand, I’ve also encountered people who are incredibly open and generous with their archives. For example, in the winter of 2023, Juan Jacobo Hernández, founder of Colectivo Sol, warmly welcomed me into his space to show me his archive and talk about the collective’s work.

So, I’m not saying these materials are entirely inaccessible, but there is a contradiction: when memory exists but can’t be shared, it starts to lose its meaning as memory.

This connects directly to the work we’re doing with Maricoteca. At its core, Maricoteca is built around the collection of queer materials that César González Aguirre has gathered over the years. The aim is not only to make this material accessible and shareable but also to approach the archive as a living entity, one that preserves the past while inviting others to contribute, reinterpret, and expand it with new material.

For example, Maricoteca will be featured in the upcoming issue of Balam Magazine (Buenos Aires), titled “RADICAL”, which focuses on the disruptive character of LGBTIQ+ archives. For this contribution, César selected a series of early 20th-century portraits that reflect the aspirations and sensibilities of their era. The images capture intimate and affectionate moments between women, marked by tenderness and honesty. Yet, within the historical context, there's an inherent ambiguity in the nature of these relationships, whether they were friendships, familial bonds, or romantic connections remains open to interpretation. The aim of Maricoteca is to explore ways of reinterpreting these materials, to give them a new life. In doing so, we begin to blur the lines between what is factual and what is imagined. I see this as a powerful strategy for engaging with queer archives, approaching them not as fixed or authoritative records, but as fluid spaces open to interpretation, imagination, and speculation.

In Archive Fever, Jacques Derrida compares the archive to the human mind, emphasizing its state of constant change. This fluidity is essential to keeping the archive alive. So, for me, when institutions or people in Mexico hold important information but don’t make it accessible, it disrupts this very notion of memory as something living, evolving, and meant to be shared.

FS: Thinking about the archive as a form of memory, and how it can lose its value if it isn’t shared, how do you make these kinds of projects public today? Is it through events? Or is there a social media component? I guess my question is more about the practical side: how do you reach the people who might be interested in engaging with this work?

CC: Taking Drama as an example, since it’s a more established project, most of the outreach has been through social media and personal invitations. For the exhibition Carmen!, which centered on Mexican celebrity Carmen Salinas, César hired a Carmen Salinas impersonator during Art Week. The three of us handed out Drama business cards stamped with the exhibition details. César and I always laugh about how extra this was, but in heinzeit, it was a fun and effective way to bring visibility to the project and engage with a broader public.

FS: What has your experience been like experimenting with different ways of sharing archival material, especially with Maricoteca?

CC: Maricoteca is still a relatively new project. Our plan is to start organizing events, not only to introduce the project to the public, but also to challenge ourselves to explore how it can function in different contexts. A key goal is to make Maricoteca public in the sense of engaging with public space: thinking about how to use that space to host events or present parts of the archive.

For us, visibility and activation go hand in hand. We don’t just want the archive to be accessible, we want it to spark conversations as a way of bringing it to life.

The fact that Drama and Maricoteca are sibling projects is also an advantage. For example, some materials from Maricoteca have already been shown at Drama, and that remains part of our vision: that the two projects can continue to complement and support one another.

FS: Now that I’m interested in learning more about archives, history, and projects happening in Mexico, I sometimes have a strange feeling about it. It’s ironic, only after deciding to live on the other side of the world do I begin to appreciate things differently and feel curious to learn more.

CC: Yeah, I really get that feeling, leaving your country and then suddenly realizing the value of its history. It happened to me, too. Our history is such a big part of our identity, and it holds so much meaning. While I was studying, my tutors thankfully encouraged me to focus my thesis on queer history in Mexico. At first, it felt strange since I wasn’t physically there, and in some ways, it even felt a bit hypocritical.

And there are definitely topics I still feel like I’m not the right person to speak about, you know? Like what you’re saying. But one piece of advice that really stuck with me, and that I still remember, came from Rosen [Eveleigh]. I told them, “I don’t know enough to write a thesis on this,” and they replied, “A thesis is also an excuse to learn something new.” I now advise this to anyone starting a research project.

And then, on the matter of authorship, who “owns” these topics or whether someone has the right to speak about them, I think that boundary is quite fluid. I mean, maybe you don’t have the knowledge of an academic, I don’t either, or the firsthand experience of the women from the Archivo de Memoria Trans who lived through the homosexual revolution, or the perspective of an art historian, and that’s okay. The important thing is to start engaging with these subjects somewhere. And remember, you can always ask for guidance and have conversations with others. We should learn from each other.

I once spoke with Estonian artist Jaanus Samma about his project Not Suitable for Work. A Chairman’s Tale, which recounts the story of an Estonian chairman criminalized for homosexuality acts during the Soviet era. The Chairman was murdered just a year before homosexuality was decriminalized in Estonia. Jaanus Samma worked with police transcripts from the trials he faced, creating a reinterpretation of his story through a fictional archive and reimagined photographs.

I asked him, “Didn’t you feel a sense of responsibility in telling this story? After all, you didn’t know him personally, and his family and friends are likely still alive. There’s a lot of room for interpretation.” He told me that the advantage of being an artist is having the freedom to bring your own voice to the material. It kind of follows the tool studied by Saidiya Hartman, “critical fabulations.” You’re not claiming, “This is exactly how things happened,” but rather offering a new lens and giving voice to histories that, because of social and political circumstances, were uncovered or silenced at the time.

I really enjoyed that conversation with Jaanus Samma because I feel queer history, by its very nature, moves beyond strict facts or objective “truth.” Instead, it embraces reinterpretation, focusing on emotions, fiction, and speculation to fill in the gaps and give voice to experiences that might otherwise be lost.

FS: It is beautiful how you say it like this. I am often doubting about how or why to work with certain topics and sometimes even question myself to the point I just don’t do it anymore. But I guess, this way of looking at it makes me understand it differently. How did you start working with queer history?

CC: During a class given by Rosen [Eveleigh] on oral history (2022), we were asked to interview someone, so I chose my grandfather. I wanted to learn more about our family history, particularly the ambiguous story behind our last name and how migration happened when my family came to Mexico. At the time, I was really interested in ambiguity, how stories shift depending on who tells them. I remember that when I was younger, my father, uncles, grandmother, and grandfather would all tell different versions of the same of our last name. No one really knew the full details, and that flexibility, the multiple versions of history, was something that fascinated me.

During one of the “Confabulations” talks, also organized by Rosen, we had a conversation with Polish artist Karol Radziszewski, who spoke about his project, the Queer Archive Institute. That conversation made me realize I felt more connected to queer history than to my own family history, or at least that it felt more personally significant. As romantic as it might sound, I started to understand that many of the rights I have today, the way I live, my friendships, and even my culture, are shaped by the struggles of those who came before me.

So, well, I’m telling you this because, in those lines, queer history is ours, right? In the sense that it’s part of our identity.

FS: Yes, I can relate to that. What is your personal relationship with queer archives, for example, in your graduation project?

CC: My graduation project [Infected Lexicon of Language] was a way of sharing my experience of living in a world shaped by heteronormativity, binary thinking, and religious structures, particularly through the lens of written language. After spending a lot of time working with the past, I wanted to ground my research in the present. My aim was to speak to specific realities that shape my life as a gay person. Part of that was also about challenging the notion of equality, because queerness often means navigating an entirely different reality. From having anal sex to still feeling afraid to kiss your partner in public, these are experiences that show how far we are from equal ground.

I believe there’s a lot of value in telling our queer histories, and that goes in hand with also sharing our personal stories. That’s why, the last time we spoke, I mentioned the idea of provocation, because for me, it’s been important to be explicit, to not shy away from intimate subjects. I think these experiences are just as much a part of the factual, they hold truth, and they deserve space in the conversation.

FS: I find it interesting what you said about working with archives, not just as a way to engage with the past, but also as a way to understand yourself and tell your own story. What role do you think graphic design plays in that process?

CC: Well, graphic design goes beyond how things look, it also has a lot to do with language, distribution, publishing, and recording. And that connects with archiving. In the program [EKA GD MA], I discovered that what interested me about graphic design was using it as a tool to explore these different methods of sharing information that commonly might be thought of as being on the periphery of graphic design, but for me, they go hand in hand.

Like, for example, with the clothing I made for the Infected Lexicol of Language, what mattered to me was the question: how can I bring the lexicon into legitimate use, how can I make it “real”? Which I think is something graphic design does, right? It bends legitimacy. It gives veracity to what we do, or the other way around. So, for this project, it was important that it looked legitimate in the sense that people would want to wear the garments. It was important for me to use living bodies as a way to distribute the terms and concepts I had created.

FS: That is very interesting, I guess it could also function as evidence.

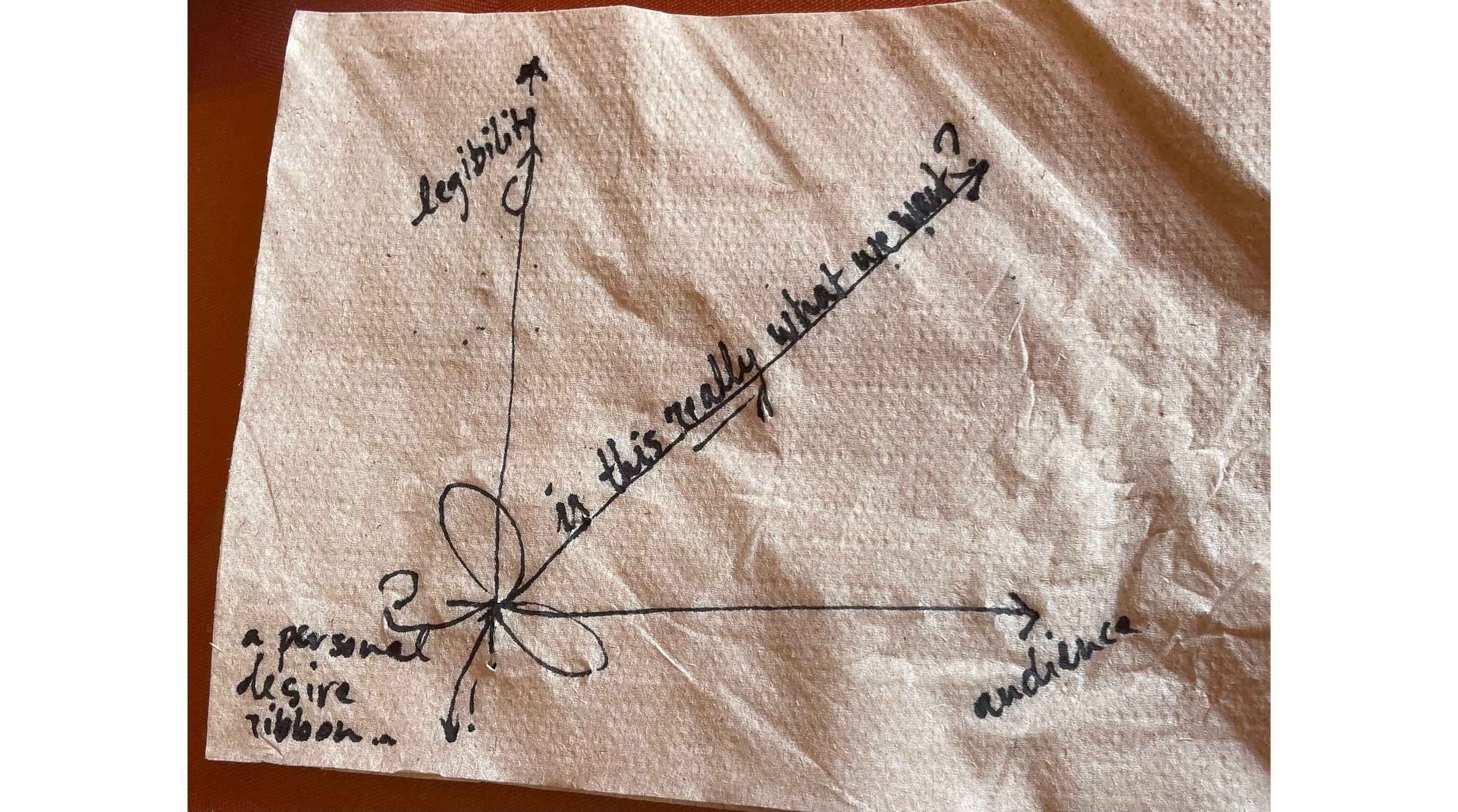

CC: Yes, exactly. For me, that’s what feels most important. I’m really interested in how information circulates and in exploring the ways information can transform into knowledge. How do we make it more tangible? How does it reach certain people, but not others? When does it rise to the surface and when does it remain invisible? It has to do with visibility and legibility. That’s my connection to graphic design.

www.memoriatrans.mx / @memoriatransmexico

www.drama.com.mx / @drama_mexicano

www.maricoteca.mx / @maricotecamx

www.infectedlexiconoflanguage.xyz / @_l_of_l